How to Set Goals and Achieve Them: What Actually Works, According to Science

Think of a goal you’ve wanted to achieve for ages. Maybe you’ve always dreamed of writing a book, starting a business, or learning how to code. But for whatever reason, you never make it further than casually mentioning it to a friend over lunch. Why is that?

For me, many goals have fallen by the wayside over the years: learning to sketch, launching a niche website, reading all 1,200+ pages of Les Misérables—the list goes on. But one goal, in particular, plagues me to this day: For 10 years, I have been trying to become fluent in Spanish. And believe me, I’ve made attempts: I took private and group lessons in Peru for three months; I’ve dabbled in Duolingo; and I attend Spanish-English conversation meetups on occasion. Despite all of this, for the past five years, I’ve made no improvements in my language level.

When it comes to how to achieve goals, there’s no shortage of advice. You’ve probably heard about the importance of setting SMART goals a million times. And yet, what does scientific research say about setting and achieving our goals? I dove into organizational behaviour psychology studies to find out. And below, I’m sharing 10 tips, backed by science, on how to successfully set and achieve goals.

10 Tips for Setting and Achieving Your Goals

1. Set Specific Goals That are Difficult With a Deadline.

Guess what? We like a challenge. According to research by Edwin Locke, the American psychologist who refined goal-setting theory, hard goals inspire a higher level of effort and performance than moderately difficult or easy ones. He also found that specific goals (e.g., “close 100 sales deals”) are more effective than vague ones (e.g., “do your best”). And if that goal has a deadline (e.g., “close 100 sales deals within three months”), even better.

2. Make Sure the Goal Isn’t Forced on You.

Particularly in work settings, goals are often externally imposed on us, and that’s a problem if we never agreed to these goals. Agreeing to a goal is known as “goal acceptance.” Researchers found that even when a goal was impossible, high accepters still achieved high performance, while low and medium accepters performed worse as difficulty increased.

In your life, you probably have expectations from family and friends about what you should be doing. Don’t mistake those outside pressures for your own personal goals. In the workplace, this research highlights why it’s so important that your team is involved in the goal-setting process and can choose their objectives, rather than having someone in management impose goals on them without their input.

3. Improve Self-Efficacy. (Believe in Yourself!)

Self-efficacy—or believing you can do it—can make or break goal achievement. Not only do people with high self-efficacy set higher goals than those with lower self-efficacy, but they’re also more committed to those goals and are more receptive to negative feedback. If you don’t believe you can achieve your goal, examine why that is. It may be that your goal is so difficult that it feels impossible; in that case, lower the target to something more attainable.

4. Gain the Skills Needed to Achieve Your Goal.

If your self-efficacy is wavering, it might also be because you lack the ability to hit your target. According to Locke’s research, people can’t achieve goals if they lack the skills and resources needed for the task. That seems obvious, but how many times do we set ourselves up for failure by trying to achieve something for which we lack the tools?

For example, last fall, I set the ridiculous goal of reading a travel memoir in Spanish. But without ever having read even a children’s book in Spanish before, I lacked the vocabulary to comprehend an entire paragraph without needing to look up words in a Spanish-English dictionary. As a result, I ended up giving the book away before I’d even made it past page two. Before attempting such a lofty goal, it would have been better for me to first equip myself with the requisite vocabulary needed to complete advanced-level Spanish reading.

5. Acquire Knowledge to Reach an End Result.

Particularly when a task is new or complex, you should set a learning goal instead of a performance goal. What’s the difference between a performance goal and a learning goal? It’s all in how you frame the instructions, according to Canadian researchers Gerard Seijts and Gary Latham.

- A performance goal focuses on a specific outcome. For example, “Get 100,000 visitors to my website by the end of the year.”

- A learning goal focuses on acquiring knowledge or skills. For example, “In Q1, learn about using SEO to drive traffic to websites.”

In one Canadian study, MBA students who set specific learning goals—such as learning to network or mastering specific course subject matter—ended up with higher GPAs and higher satisfaction than the MBA students who had only set a year-end GPA goal.

For my Spanish goal, instead of saying, “I want to become fluent,” it would be much more helpful to say, “Each month, I will learn 100 new words.”

6. Check Your Motivation.

Is your motivation intrinsic or extrinsic? In their seminal work on motivation, researchers Richard Ryan and Edward Deci offer the following definitions:

- Intrinsic motivation is “doing an activity for the inherent satisfaction of the activity itself.”

- Extrinsic motivation is “the performance of an activity in order to attain some separable outcome.”

You may wonder: Does it matter whether I’m intrinsically or extrinsically motivated if the end result is the same? If your goal involves learning, then yes, it does matter.

Kou Murayama, a researcher at the Motivation Science Lab at the University of Reading, ran a series of behavioural experiments to determine how these two types of motivation affect learning. In one study, he examined survey data from more than 3,000 students in German schools. Items focused on performance (“In math I work hard, because I want to get good grades”) were linked to immediate math achievement scores, while items focused on mastery (“I invest a lot of effort in math, because I am interested in the subject”) were linked to growth in math achievement scores over the next three years. Notice how performance (getting good grades) is extrinsic, while mastery (interest in the subject) is intrinsic.

These results were aligned with findings from Murayama’s own lab, showing that while performance-based motivation may work for short-term learning, mastery-based motivation makes learning last in the long run.

So if you’re failing to meet a goal, ask yourself why you want to achieve that goal. Is it because you genuinely find it valuable or interesting? Or is it because of some external reward, and now that it’s been withdrawn, you no longer care for the goal?

7. Frame Goals and Feedback in the Positive.

Frame a tough goal as a challenge rather than a threat. Researchers in Israel found that students who viewed a goal as a challenge (focus on success) outperformed those who viewed the same goal as a threat (focus on failure).

How do you induce challenge rather than threat? Frame the instructions and results in a positive way. For example, instead of saying, “There’s a 55% chance of failure,” say, “There’s a 45% chance of success.” Or, instead of saying that your goal is to “stop being lazy,” change it to “be more productive.”

Further, research shows that focusing on positive outcomes improves task performance and makes you more likely to persevere toward your goal.

- In study one, those whose goals were framed positively spent more time attempting to succeed at the task.

- In study two, those who received positive-outcome-focused feedback performed better and persisted for longer. For example, after failing to solve an anagram correctly, participants in the positive feedback group were told, “You can still make it—you just need two more.” But those in the negative feedback group were told, “Try not to miss any more or you will fail to reach the goal.”

Instead of berating yourself with, “If I don’t achieve this goal, my teammates will be angry,” try, “If I achieve this goal, I’ll be helping my teammates.” Positive framing is much more likely to give you the boost you need to persevere.

8. Create an Action Plan.

If you want to reach your goals, you need to understand the difference between these two things:

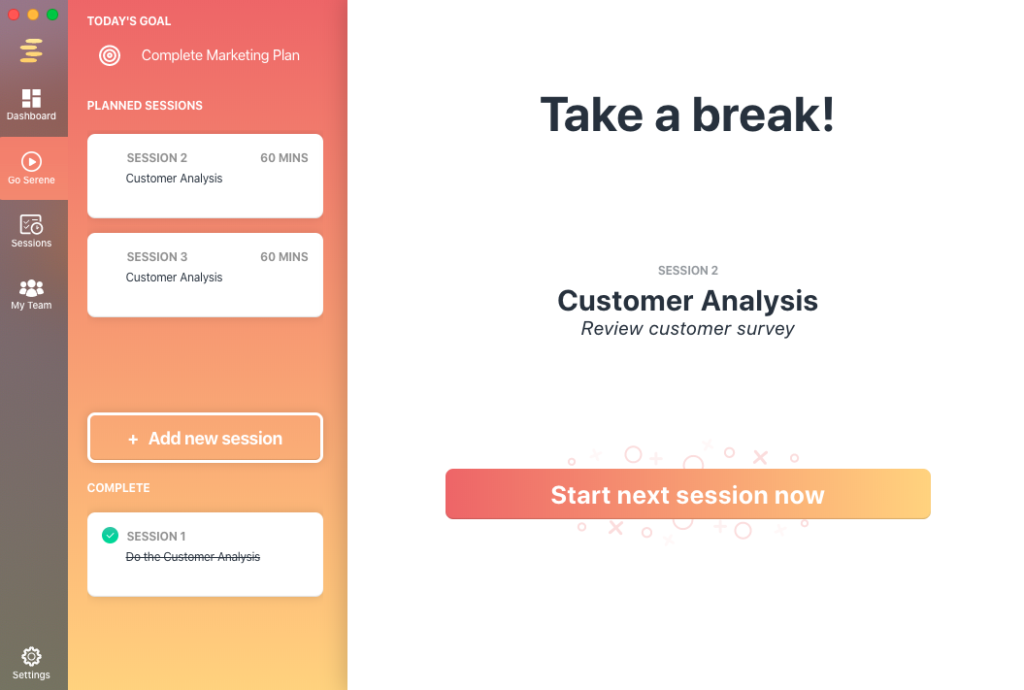

- Goal intention: “I want to learn to code.”

- Implementation intention: “I will complete one lesson of an online coding course in my home office at 7 a.m. before I go to work.”

Studies have shown that having an implementation intention—a specific action plan, including the how, when, and where—drastically increases the chances that you’ll enact the behaviours required to reach your goals.

For example, my saying, “I want to become fluent in Spanish” isn’t enough. A helpful implementation intention would be, “I will attend a one-hour private Spanish lesson online at 7 p.m. every weekday.”

Implementation intentions and action plans are just other ways of saying that you must develop the habits that support your goals.

9. Find Yourself an Accountability Partner.

Psychology professor Dr. Gail Matthews conducted a study of 149 professionals with various business-related goals, from reducing work anxiety to increasing income. Of the five experimental groups, the highest-achieving group was the one that did all of the following:

- Wrote their goals

- Rated their goals on difficulty, importance, and other factors

- Formulated action commitments

- Sent their goals, action commitments, and weekly progress reports to a supportive friend

That last part about sending progress reports to a friend is key; having someone to hold you accountable for your goals can increase your chances for success. In a University College London study of couples, when one partner developed a healthy habit, the other was much more likely to develop it too. Try spending time with at least one person who is trying to make the same positive change, compare learnings and ask them to check in with you regarding progress toward your goal.

10. Celebrate Small Wins.

Okay, so maybe you’ve set a hard and specific goal, are intrinsically motivated, created an action plan, and found an accountability partner—but you still haven’t reached your goal. What gives?

It may be that you need to see proof of your progress. Personal finance experiments have shown that people who are trying to get out of debt are more likely to reach their goal if they start with one account and the smallest amount, rather than trying to disperse payments across all accounts or tackle the largest amount first. Why? It’s because Seeing progress, even if it’s small, enhances motivation.

Researchers Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer have a name for this: the progress principle. In their words:

“Of all the things that can boost emotions, motivation, and perceptions during a workday, the single most important is making progress in meaningful work. And the more frequently people experience that sense of progress, the more likely they are to be creatively productive in the long run.”

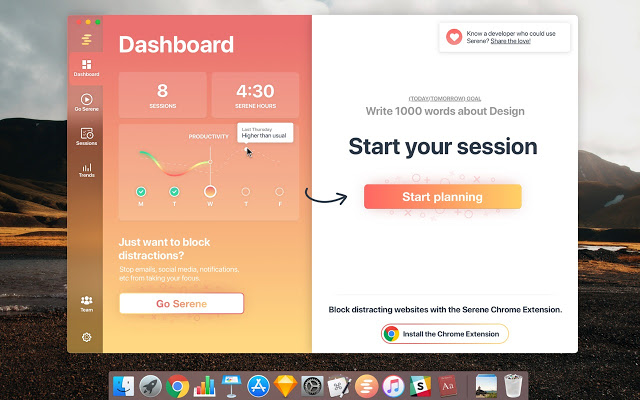

So whatever your goal is, track your progress—whether that’s in a spreadsheet, an app, or on paper—and celebrate the small wins. When the going gets tough, you can pull out your progress log and see concrete evidence that you’re making headway toward your goal.

How Will You Take Action Toward Your Goal?

At the beginning of this article, I asked you to think of something you’ve wanted to achieve for a long time. Now that we’ve gone over 10 evidence-based tips for reaching your goals, I want to leave you with this challenge: Instead of just thinking about your goal, choose one of the suggestions we learned today and start taking action toward it.